-

A Letter from the Jolly Corner

Amândio ReisUniversidade de Lisboa Henry James’s final ghost story features a very important—but pointedly lost and irretrievable—epistolary text. James’s expatriate protagonist, Spencer Brydon, is dogged in his pursuit of a projected, All-American Doppelgänger, and haunted by the memory of an unopened letter. This letter is mentioned only once in the story, but its significance for the protagonist, as…

-

Isak Dinesen’s Script

Brian Gingrich There is a moment in “Babette’s Feast,” one of the best-known stories by Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), when a character named General Lorens Loewenhielm stands up, slightly drunk at the end of a lavish dinner, and gives a speech to the other guests, all elderly members of a pious religious sect. The reader…

-

Mirror and Dialogue, Techniques of Selfhood

Bernardo Diniz Ferreira Bringing together Machado de Assis’ “The Mirror” and Clarice Lispector’s “If I Were Me” begs a comparison between two techniques of selfhood: the mirror and the dialogue. Both are timeless engenderers of alternate selves, houses of reflection. Machado’s tale unfolds their difference; Lispector’s provides an interesting answer and counterpoint to Machado’s handling…

-

Transformations Beyond ‘Nature’: Seamus Heaney’s Medieval Poetics

Jill WhartonApril 2021 Throughout his career, Seamus Heaney invoked medieval literary allusion, adaptation, and translation to punctuate his iterations of Irish history.[1] And not, as one might expect, to catalyze a nostalgic sense of lost authenticity, but extensively and strategically, to transformative structural ends. To elucidate a ‘transformation’ is to speak of the coeval nature of…

-

Atlantics

Bernardo FerreiraUniversidade de Lisboa Regarding the supernatural mystery of Mati Diop, I am reminded of the words with which, in the 18th century, Thomas Browne opens his Pseudodoxia Epidemica: “Would Truth dispense, we could be content, with Plato, that knowledge were but remembrance; that intellectual acquisition were but reminiscential evocation, and new Impressions but the…

-

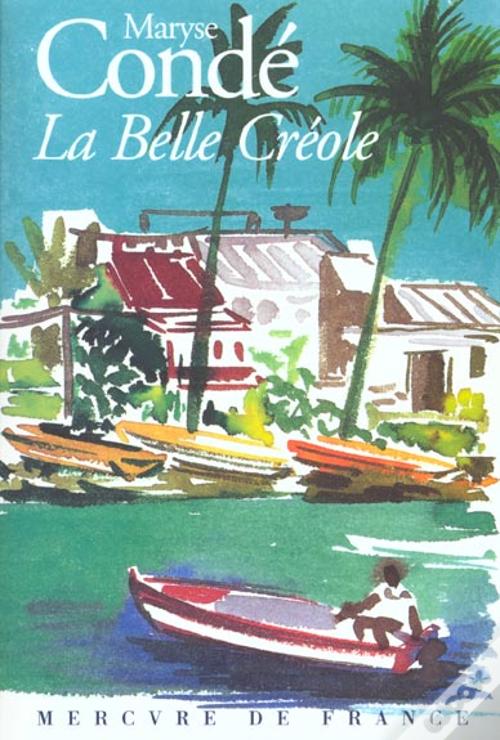

Guadeloupe on the Margins

Jill WhartonJanuary 2021 (Para ler este texto em português, clique aqui.) Maryse Condé’s The Belle Créole was published in French in 2001, but did not appear in English translation until early 2020, a surprising lapse when we consider Condé’s celebrated literary status, prolific output, and career of elite academic appointments. In what follows, I survey several of The…

-

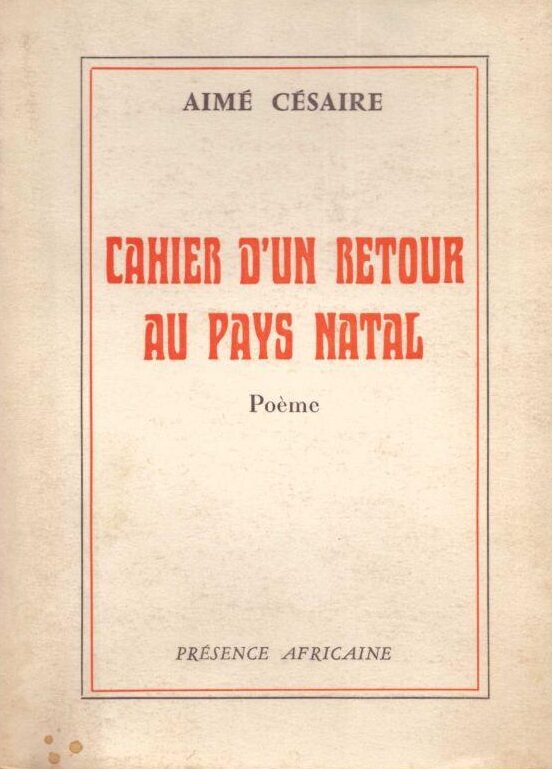

Christmas with Césaire

Amândio ReisUniversidade de LisboaDecember 2020 (Para ler este texto em português, clique aqui). In his most celebrated work of poetry, Notebook of a Return to the Native Land (Cahier d’un retour au pays natal), French writer Aimé Césaire speaks of a return to the island of Martinique, where he was born. Considering his choice of words, we may assume a return is less grounded, and more haphazard, than the return would be. It…

-

Seamus Heaney, “Making Strange”

Seamus Heaney’s “Making Strange”, from Station Island (1984), has served as one interpretive touchstone for our latest workshop on the theme of “Displaced Selves”. Heaney’s meditation on how identity is informed by the experience of travel, the tensions of cultural exchange, and the affordances of intellectual encounter, enriched our understanding of the texts and films…