Bernardo Diniz Ferreira

Bringing together Machado de Assis’ “The Mirror” and Clarice Lispector’s “If I Were Me” begs a comparison between two techniques of selfhood: the mirror and the dialogue. Both are timeless engenderers of alternate selves, houses of reflection. Machado’s tale unfolds their difference; Lispector’s provides an interesting answer and counterpoint to Machado’s handling of selfhood as a tragedy of mistakes.

We might think of self with two premises: a self can be an inner entity who beholds, in its own phenomenal space, the world, as well as become the beheld object itself. Our self beholds a self, and this beholding can take the form of a tension between what we believe ourselves to be and those actions which we might deem out of character. This inside/outside dichotomy frames the opening to “The Mirror,” in which two places are characterized by a distinct quality of light: “the room was small and lit by candles, whose glow mingled mysteriously with the moonlight streaming in from outside.” Like the soul, these two qualities of light “mingle mysteriously,” and this new double-light grounds the text’s central questions of legibility, resting between (if not the mirror and the lamp) the mirror and the candle.

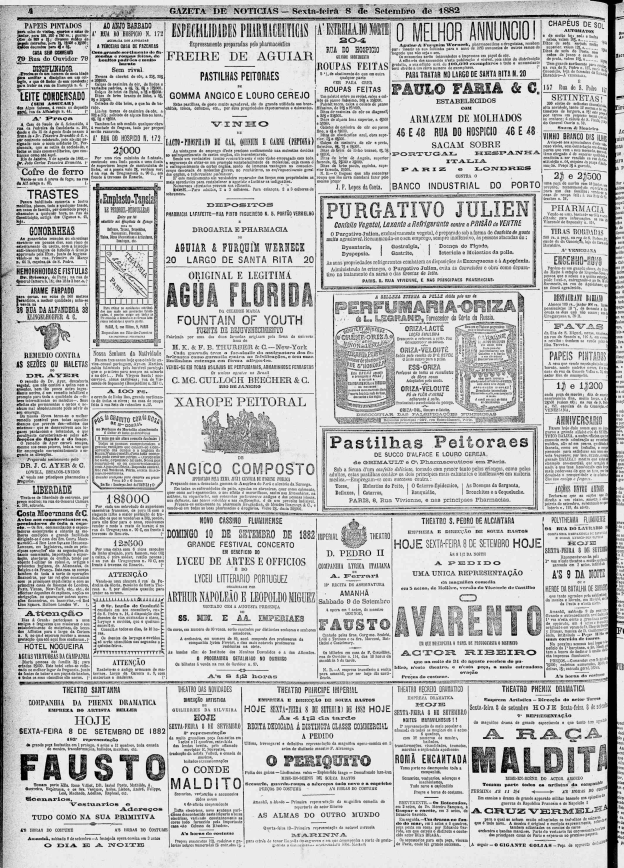

“The Mirror,” in accordance with Jacobina’s compulsive misreading, is a willfully obverse retelling of Plato’s Symposium. A number of men gather after dining and happen to discuss the nature of the human soul. Aside from Jacobina, they do it in a cordial and friendly way, as the opening paragraph stresses twice, juxtaposing the relaxed mood of the meeting with the depth of the philosophy at play. Someone will propose that the soul should be doubled — Jacobina reprises the role of Aristophanes’, whose beautiful contribution imagines humans as lonely souls seeking their ancestral pair. But while Jacobina’s monologue claims to be about the duality of all souls, he does not realize that he speaks as someone who has reached his goal in singularity, not only as a result of his weird tale, but also because he refuses to engage in dialogue — a sharp departure from Aristophanes. In a paratextual coincidence, the tale that follows “The Mirror” in the 1882 collection is titled “Alcibiades’ Visit.” In Plato’s text, Alcibiades arrives late to the debate, much like in Machado’s book he arrives only when the tale is already over. In “The Mirror” he cannot join the discussion, as its end had already been precipitated by the protagonist’s sudden disappearance.

Other references further weave this string of misunderstandings: the off-hand remark that “the best definition of love is not worth a girlfriend’s kiss” inverts the main point of Diotima’s lesson on Erôs, that through the love of beauty, the lover can progress from the desire for earthly bodies up until the Form of love itself, the beauty of beauty – a girlfriend’s kiss is the first step towards a philosophical understanding of love. Another reversal: contrast the two mules who philosophize while shaking away flies with Socrates, the original gadfly of Athens. These are two examples of Jacobina’s materialism and anti-intellectualism, traits of a character who defines his humanity by his uniform and converses on the condition that others do not answer him: “I never engage in arguments,” he says, “but if you will listen in silence, I can tell you about an episode in my life that demonstrates the issue in question in the clearest possible terms.”

Mirror and discourse become two distinct, mutually reinforcing, techniques of selfhood, of self-making. Like Bram Stoker’s count (roughly contemporary to Machado’s collection), Jacobina’s absent reflection stands for an inhumane absence of soul. Their vampiric quality is similarly grounded on class parasitism and social hierarchy. The mirror-object — and its historical baggage — melds this individuative process into the formation of collective identity: in 1808, the Portuguese court was exiled in Brazil. The outcome of the pressure and demands of hundreds of newly-arrived courtiers is mixed: Brazil’s global standing as a colony is reinforced (its independence imminent) but so is the weight of slavery on a society already dependent on such labour practices. The Portuguese mirror, in which you “still see the gilding, eaten away by time,” reflects Jacobina, a man whose fragile identity is null without slaves to prop it up.

But what mirrors are like when alone, paraphrasing Rilke, can also be the source of the inexhaustible thing, of poetry — of the ability to jump over the mere reflection and engender oneself out of nothing. Jacobina briefly recognizes, but fails to espouse, such a possibility. Obsessed with the exterior soul, he takes up writing, unavailingly; on being inquired on his nourishment, he retorts that he vociferously recited verses — but his list of chosen works betrays mindless quantity rather than quality, it suffers from the same problem as the paper — an imbalance between the black ink of the text and white paper of the page, content and form:

At one point, I considered writing something (…) But the style, like Auntie Marcolina, would not come. Sœur Anne, sœur Anne… Nothing at all. All I could see was the ink turning blacker and the page whiter.

Purely physical and deprived of the feeling of poetry, he abandons all poetic endeavors, brags that by putting on the uniform, he managed to overcome the six remaining days of solitude without feeling them. As he had noted before, “facts will explain the feelings, facts are everything.”

In Clarice Lispector’s text, conversely, to feel is the appropriate point of departure for the ethical inquiry – even as it displaces the practical task of finding the “important” paper. There are no Jacobinean false-dichotomies: the paper — its importance and storage — may fall squarely on that world of “facts,” but the promise of knowing selfhood rests on the recognition of the external action of safekeeping the paper:

When I don’t know where I have kept an important paper and the search becomes useless, I wonder: if I were me and I had an important paper to keep, which place would I choose to keep it? Sometimes it works. But sometimes I get so impressed by the phrase “if I were me,” that the search for the paper becomes secondary, and I start to think, I mean I start to feel.

Unlike Jacobina, Lispector proposes that the real self is a blindspot between what we are and what we do; or it is both, or neither, simultaneously.

In another text titled “Fernando Pessoa Helping Me” (21 September 1968), she compares (unfavourably) the writing of weekly columns to the writing of books, remarking that she cannot but reveal who she truly is whenever she signs her name. “Will I lose my secret intimacy?” If so, “what to do?” A quote from Pessoa brings a modicum of solace: “To speak is the simplest way of becoming unknown.” The doubling of the self, for Lispector, starts with a conversation-opening question. As the text opens, she asks herself, and promptly asks us as well, for despite the monologue nature of the weekly newspaper column, what follows should be a conversation with a world of readers — a notion she expounds in a different text (“To Be a Columnist,” 22 June 1968). Lispector talks to us, her readers, and thus also to herself.

This dialogic technique of selfhood creates a self, just as it erases another. One is brought forth in the posing of a question, alternatives disappear as it answers. “If I were me I would give everything I have,” she writes. The becoming of who one is represents this entry into the ineffable feeling, larger than thought, a form of self-estrangement: one un-knows in order to know oneself; we risk becoming unrecognizable to our acquaintances and to ourselves. Lispector’s emphasis on this dialectic returns the reader to the tension Machado underscores on the matter of style – which Jacobina pointedly lacks. To have a style is also to be recognizable when doing something new. Our friend or beloved does something we could not have predicted, but which we, nevertheless, recognize as their character: we recognize their ‘signature’ style. It is crucial to preserve spaces in which we might become unrecognisable. Friendly conversation among equals and essayistic writing are two examples of performative stages where character might rehearse it(s)self freely.

Lispector’s essay ends with a smile, an odd reaction for someone just now so close to the “full pain of the world” and also the opposite of Jacobina’s terror. Might the difference be explained also by a distinct approach to the necessity of pain? Lispector’s leap of faith involves a harmonization of the pain before, and the pain after – to become who we are is to enter a dialogue of pain and feeling: the pain of the world, of this new-self firmly rooted in it, but also the pain once held in our not-self, out of feeling’s sight. “I pinched my legs, but the effect was only a physical sensation of weariness or pain, nothing more,” says Jacobina. When he (feverishly roleplaying as the wife of Perrault’s Bluebeard) calls for “sister Anne,” might he be looking for this secret room, whose door, as the tale goes, is opened by a key dipped in blood? But he, not Bluebeard, had concealed this haunted room. He fails to realise that he should rather, like Lispector, call – ask – for himself. And if in-between the pain of the world and our secret pain lies the pain of others, this too is ignored by Jacobina, who quickly discards the notion of meeting with his aunt.

In describing the real self, Lispector does not once use the verb to feel. This true “I” experiences and has (a uniform, perhaps), but it does not feel. In the final sentence, however, it is reused twice, in a gradating retreat: I felt myself smiling is an involuntary movement that the second “felt” has delivered unto a familiar shape. The bridge of feeling leads to an unknown; would feeling be waiting for us on the other side? There may be solace in believing that it is reserved for the self who is not yet – and that its loss might be a price too incommensurable to pay in order for one to become who one believes themselves to be.

Summary in Portuguese

A aproximação entre “O Espelho”, de Machado de Assis”, e “Se eu fosse eu”, de Clarice Lispector”, solicita uma comparação entre duas técnicas de individuação: o espelho e o diálogo. Ambos são eternos fabricadores de eus alternativos e moradas da reflexão. O conto de Machado explora a diferença entre eles; o texto de Lispector oferece uma resposta e um contraponto interessantes ao tratamento de Machado da individuação enquanto tragédia de enganos. Podemos pensar no eu a partir de duas premissas: um eu pode ser uma entidade interna que, no seu próprio espaço fenoménico, observa o mundo, ou pode tornar-se o próprio objecto da observação. O nosso eu observa um eu, e esta observação pode assumir a forma de uma tensão entre aquilo que acreditamos ser, nós mesmos, e certas acções que possamos julgar como incaracterísticas. Esta dicotomia interior/exterior enquadra a abertura de “O Espelho”, na qual dois espaços são caracterizados por meio de uma distinção na natureza da luz: “a sala era pequena, alumiada a velas, cuja luz fundia-se misteriosamente com o luar que vinha de fora.” Tal como a alma, estas duas qualidades da luz “fundiam-se misteriosamente”, e esta nova dupla luz alicerça as questões centrais, no texto, de legibilidade, colocando-se entre (se não o espelho e a lâmpada) o espelho e a vela.