Compass | INCH Online Journal

-

A GRAFFITI OF GREAT ANTIQUITY

A Graffiti of Great Antiquity Paul Cunningham “The gloom of cypresses,is what i wish to prove”– Eavan Boland drifting is a matter of cloud-murkwhen standing in the ruinsof the oldest city imaginablea longtime search for easy crossingfrom spring to winterthe yearly glow of former timesthe very real cargo of weaponsdrifting is how wedance together in the…

-

Alternative Selves – video #1

In these last couple of months we asked some of the PhD students and researchers involved in INCH to tell us what they thought of the last two cycles of our seminar – on the theme “Alternative Selves”. We chose to do this through video, which has been – unfortunately – a lingering necessity in…

-

Odyssean Greyhounds

by Marie Shelton, University of Notre Dame The summer before I started college, I quit my job and boarded a Greyhound from San Diego to Boston. The journey took two and a half days. I stopped in LA, Vegas, Denver, Kansas City, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and New York to refuel. When I…

-

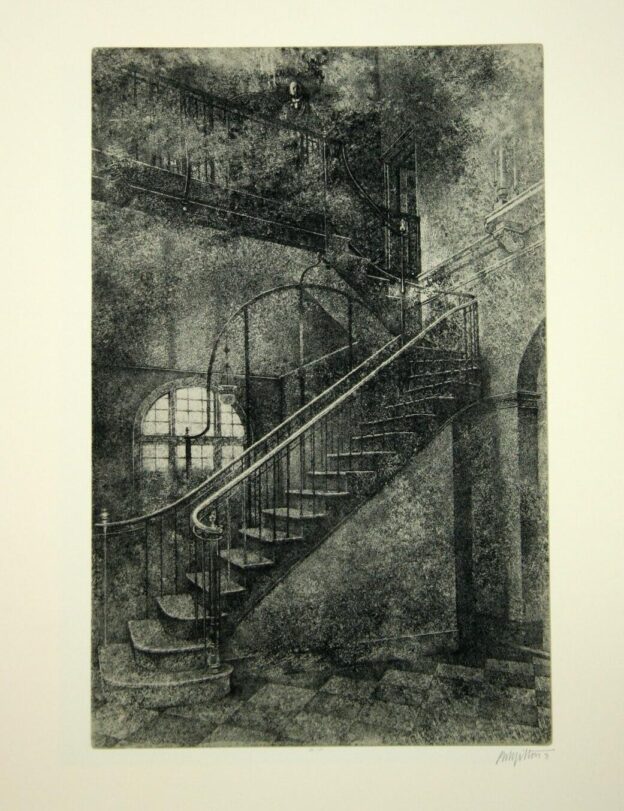

A Letter from the Jolly Corner

Amândio ReisUniversidade de Lisboa Henry James’s final ghost story features a very important—but pointedly lost and irretrievable—epistolary text. James’s expatriate protagonist, Spencer Brydon, is dogged in his pursuit of a projected, All-American Doppelgänger, and haunted by the memory of an unopened letter. This letter is mentioned only once in the story, but its significance for the protagonist, as…

-

Isak Dinesen’s Script

Brian Gingrich There is a moment in “Babette’s Feast,” one of the best-known stories by Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), when a character named General Lorens Loewenhielm stands up, slightly drunk at the end of a lavish dinner, and gives a speech to the other guests, all elderly members of a pious religious sect. The reader…

-

Mirror and Dialogue, Techniques of Selfhood

Bernardo Diniz Ferreira Bringing together Machado de Assis’ “The Mirror” and Clarice Lispector’s “If I Were Me” begs a comparison between two techniques of selfhood: the mirror and the dialogue. Both are timeless engenderers of alternate selves, houses of reflection. Machado’s tale unfolds their difference; Lispector’s provides an interesting answer and counterpoint to Machado’s handling…

-

Transformations Beyond ‘Nature’: Seamus Heaney’s Medieval Poetics

Jill WhartonApril 2021 Throughout his career, Seamus Heaney invoked medieval literary allusion, adaptation, and translation to punctuate his iterations of Irish history.[1] And not, as one might expect, to catalyze a nostalgic sense of lost authenticity, but extensively and strategically, to transformative structural ends. To elucidate a ‘transformation’ is to speak of the coeval nature of…

-

Mr. Ripley and the Banality of Talent

[Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley, 1955] Maria ApostolidouUniversity of Ioannina Coming across The Talented Mr. Ripley for the first time, the unsuspecting reader might anticipate a story about a central character named Ripley or, in other words, a novel that focuses on the life and opinions of a specific person. As the reading progresses, however, the reader’s…

-

Fighting the Circle

Thoughts on Displacement in Britten’s Owen Wingrave Bianca De MarioUniversità degli Studi di Milano 1971, May 16th. Owen Wingrave, an opera for television composed by Benjamin Britten, directed by Brian Large and Colin Graham and produced by John Culshaw, is broadcast on BBC Two England. Much like The Turn of the Screw the subject was inspired by an unusual…